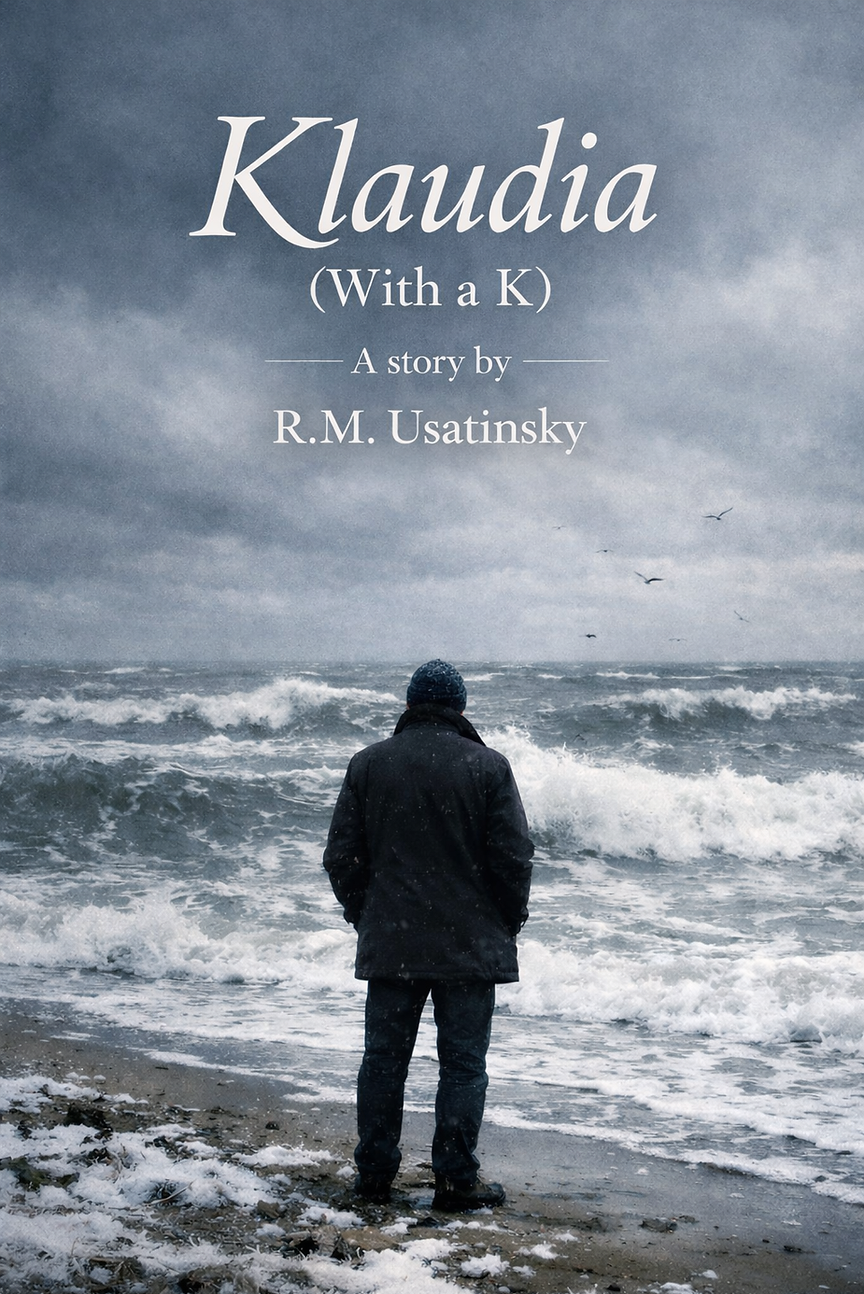

There was no good reason for me to leave the house on what was a blistery, wet winter morning, other than wanting to avoid seeing my former brother-in-law who had driven up from Limburg to drop off his daughter who was spending the few last days of the mid-February school holiday with my three youngest daughters. And of all the things I could have done—like visit the newly opened café in the village (did they name it Lily’s?)—I chose to get on a bus and make my way to the beach for pofertjes.

When I arrived at the Pannenkoekenhuis Kijkduin, I took a table facing the wavy green North Sea and was quickly approached by a lovely young woman who greeted me in English with an equally lovely Eastern European accent I couldn't quite place. I quickly replied jak się masz, telling her I was from the second largest Polish populated city outside of Warsaw. She stopped, tilted her head (that particular tilt that young women deploy when they're deciding whether to be charmed or suspicious) and then smiled.

Jestem Klaudia, she said. With a K.

And just like that, the blistery morning had a reason for existing.

I ordered hot cocoa and pofertjes I didn't particularly need, and sat there watching the North Sea do what the North Sea does—which is to say, make everything feel both enormous and beside the point—and I thought about what if. Not in the catastrophizing way I'd spent most of my sixties up to this point thinking about it, the what if of diagnoses and estrangements and the slow subtraction of people you assumed would always be there. A different what if. The kind that feels less like a question and more like a door left slightly ajar.

It was a Thursday. This matters, though I couldn't tell you precisely why. Thursdays have always felt to me like the day the week finally decides what it actually is—not the false promise of Monday, not the relief of Friday, but something more honest. Something that looks you in the eye.

She came back with the cocoa. We talked. I won't pretend I remember exactly what was said as I was too busy noticing things. The way she looked at me like the way you look at old friend you haven’t seen for years. The fact that she wasn't performing anything. There's a kind of ease that very young people sometimes have, before the world has sufficiently complicated them, that older people either find threatening or find intoxicating. I am, apparently, still capable of finding it intoxicating. This struck me as excellent news.

Now. I am not a fool. Or rather, I am occasionally a fool, but I am a self-aware fool, which I've always considered the more defensible variety. I know what a man my age sitting alone at a seaside pancake restaurant looks like when he starts chatting up the waitress. I know the statistics on May-December romances, the raised eyebrows, the whispered what does she see in him, the unwhispered assumption that what she sees in him is a shortcut to something, a passport, a stability, an exit from a harder life. I know all of this. I also know that knowing something and knowing something are two entirely different cognitive experiences, separated by roughly the distance between here and Białystok.

Here is what I believe about fate, for whatever it's worth from a man eating pofertjes alone on a Thursday in February: fate is not the thing that happens to you. Fate is the thing you recognize, in the moment it's happening, as something you were always moving toward. It doesn't announce itself with trumpets. It announces itself as a young woman named Klaudia—with a K—asking if everything is to your liking, and you saying yes, though the cocoa is slightly too sweet and the pofertjes have gone a little cold and none of that matters even slightly.

Why not, you ask. Well. Let me count the ways.

I am older than her father almost certainly is. I have children (two of whom are clearly older than she is) who would receive this information with expressions I can already perfectly visualize and would prefer not to. I have a body that has begun the long, unglamorous process of renegotiating its terms. I have—and I say this with what I hope reads as rueful humor rather than self-pity—a somewhat abbreviated timeline in the broad statistical sense, the specific parameters of which I won't bore you with here, though they do occasionally bore me at three in the morning when sleep has better things to do than visit and my bladder requires my attention.

And yet. And yet is the most important phrase in any language. I've checked.

What would it mean for a young woman—a whole young woman, unlived life stretching ahead of her like the North Sea, green and enormous and going somewhere—to choose this? To choose me? Not the version of me I was at thirty, which I will tell you was, if not impressive, at least less complicated. The version I am now. The one who takes two buses to the beach on a blistery winter morning to avoid family obligations and sits alone ordering things he doesn't need and notices, still—still—the way a woman tilts her head when she's deciding whether to be charmed.

I don't think the answer is pity. I refuse to believe it's pity. I think, if I'm being uncharacteristically direct about it, the answer might be that some people—some rare, particular people—understand intuitively that love is not a retirement plan. That it is not optimized for longevity or convenience or the approval of people who use words like appropriate. That what an older man who has survived himself can offer—attention, stillness, the hard-won knowledge of what actually matters—is not nothing. Is, in fact, not nothing at all.

She came back a second time. A third. Each time with the particular purposefulness of someone who has other tables to attend to but is choosing, in small increments, not to. I noticed this the way you notice weather changing, not with alarm, but with a kind of whole-body attentiveness. The cocoa was long finished. The pofertjes a memory. I had no remaining business being at that table.

And then I caught her eye. Not accidentally. Let's be clear about that. I am a man who has blundered into many things in his life—marriages, cities, conversations he had no business starting—but this was not a blunder. This was a decision. Small, perhaps. The size of a glance. But a decision nonetheless, made by a man who has learned, at considerable personal expense, the difference between the two.

She came over. I asked for the bill.

In our final conversation I learned that she was not in school. That she was considering studying history or chemistry but the cost of school was too high. The combination struck me as either perfectly contradictory or deeply logical, depending on how you think about the nature of things—history being the study of what people did with their time, chemistry being the study of what happens when certain elements come into proximity with certain other elements. Make of that what you will. I have made quite a lot of it, in the hours since. The age question I did not ask directly. But history or chemistry, not yet in school, the way she carried herself without any of the performative uncertainty that tends to cluster around very young people still auditioning for their own personalities; I put her somewhere between nineteen and twenty-five and left it there. A continent, not a pinpoint. Plenty of room.

She mentioned she used to read but no longer had time.

I feigned annoyance. I want to be precise about the word feigned—it was a performance, yes, but the way all the best performances are: rooted in something genuine. Because the idea that a person who wants to study history or chemistry has no time to read does genuinely annoy me, in the way that small surrenders to circumstance always annoy me, because I have made so many of them myself and recognize the shape of the excuse.

I reached into my backpack.

I carry a copy of my novel with me. I do this not out of vanity—or not only out of vanity—but because you never know. Life being, as previously established, a series of arrivals you didn't know you were heading toward. The book was there. She was there. The North Sea was doing its enormous indifferent thing outside the window. It seemed like the most natural transaction in the world.

I told her she must find time to read this. And then she must send a note to the website on the copyright page.

She looked at the book. Looked at me. Asked if it was mine.

Not anymore, I said. It's yours now.

And then I shook her hand. Formal. Warm. Unambiguous. Told her to have a nice day. And I turned for the door. And then, with my hand already on it, the cold already leaking in around the frame, I turned back just enough to tell her that if she checked the website in a few days, there would be something there.

She looked up from the book.

For me? she said.

And she was beaming. I want to stay with that word a moment because it's the right one and I won't improve on it. Not smiling. Not pleased. Beaming—the kind of expression that comes from somewhere below calculation, before the face has had time to decide what it's supposed to do. Unguarded. Genuine. The expression of someone who has just learned that they were seen.

Yes, I said. For you.

And then I walked out into the icy winter and the stinging mist and I headed for the bus stop, and I did not look back, and the cold hit me like a verdict, and I was, there is no other word for it…happy. Not the cautious, provisional happiness of a man who has been disappointed enough times to keep it on a short leash. Something older than that. Something that knew what it was.

The 26 bus came. I got on. I found a window seat and watched the dunes go by, gray and stoic in the February light, and I thought about a young woman named Klaudia—with a K—holding a book with my name on the cover and a website on the copyright page and approximately fifty-five thousand words of evidence that I am a person worth knowing. I thought about history and chemistry. I thought about the particular courage it takes to hand someone a door and then walk away and let them decide whether to open it.

I thought about the brother-in-law I'd been avoiding all morning, who was probably still at the house, drinking my coffee and occupying my sofa with the comfortable entitlement of a man who has never had to take two buses to the North Sea to remember who he is.

Two buses home. The same dunes in reverse. The same gray light. And somewhere back there, in a pancake house on the North Sea, a young woman named Klaudia was holding a book and thinking about a website and waiting—perhaps without quite knowing she was waiting—to see what came next.

As was I.

As was I.